FICTION: LITERARY OR GENRE?

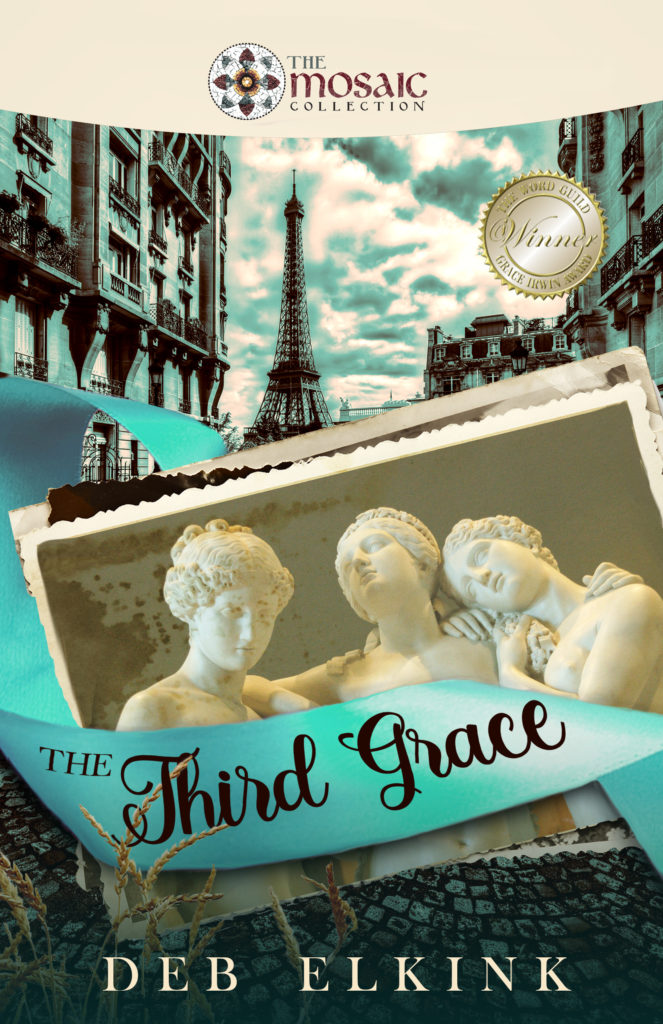

Back in 2010, when my newly acquired agent asked for the genre of my debut novel (The Third Grace), I identified it as literary fiction. He immediately corrected me: “No, no. We’ll call it contemporary women’s fiction. No one today reads literary fiction.”

I almost gasped. Was it true? My own library was full of literary titles, my writing brain of literary characters and themes:

- Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights with Heathcliff’s smouldering passions teaching me about the human condition and societal influences (the author’s one and only novel);

- Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter exposing Hester Prynne’s shame inside the punitive culture of the New England colony (imbued with Christian and religious themes);

- C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia with Aslan pointing to a transcendent world beyond our physical realm (a fantastical series heavy on symbolism).

I loved literary fiction’s motifs, tropes, and allegories conveying abstract ideas—the physical story hinting at the metaphysical meaning demanding active reader learning rather than passive entertainment. But at the point of publishing my first novel, I didn’t yet understand the difference between genre and literary—the two fiction classifications known to the world of general publishing.

Of course, what my agent really meant when saying no one reads literary fiction nowadays was that literary fiction doesn’t sell widely and that publishers must, above all, sign multi-title authors who will produce many books—and genre fiction sells more than literary.

This distinction between genre and literary fiction came into being only in the twentieth century, when publishers began to use labels for mass marketing. Publishing houses were seeking the next bestseller, so they developed main categories (securing genre authors with huge advances):

- Romance (e.g., Nora Roberts)

- Mystery and Crime (e.g., John Grisham)

- Science Fiction and Fantasy (e.g., Ray Bradbury)

- Horror and Thrillers (e.g., Stephen King)

- Westerns (e.g., Louis L’Amour)

- Historical (e.g., Ken Follet)

- Young Adult (e.g., Judy Blume)

What actually is genre fiction?

In broad terms, genre fiction is popular narrative focusing on entertainment and written within the narrow specifications of each category. For example, in general:

- Horror intends to arouse reader dread, terror, even repulsion;

- Mystery/crime centers on the investigation and resolution of criminal acts;

- Romance is about love relationships with happily-ever-after endings.

What is literary fiction?

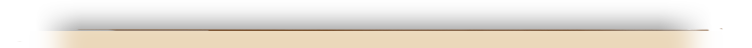

In contrast, literary fiction is a bit fuzzier to define, aspiring to be artistic; it emphasizes meaning through character, theme, and story style over plot action and prescribed outcomes. In literary fiction, you might find:

- Ambiguous endings not always neat and clear;

- Plot structure not necessarily following rules of particular genres;

- Exploration (sometimes unresolved) of ideas, philosophies, aesthetics, conceptions, and social/political commentary.

Can’t genre and literary fiction overlap?

Of course, the rigidity of black-and-white genre rules versus the open-ended nature of literary fiction blends in all manner of grey tones. We see this fusion when we consider literary titles employing subgenres, or genre stories adopting literary approaches. Take, for example, these blockbuster genre novels of great literary value:

- All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr is considered historical fiction, its subgenres including suspense and survival. On a literary level, Doerr’s lyrical style encompasses sensuous detail and employs a nonlinear plot structure, ethical and political critique, anti-war themes—and a blighted romance.

- Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens is a murder mystery with a coming-of-age subgenre, yet Owens’s literary style poses two timelines through atmospheric setting, symbolism around wild animal behaviour, and themes of justice and loneliness.

- The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien is wildly popular and one of the best-selling books of all time. It’s what I would call literary fiction but is known as a classic of the fantasy genre. LOTR is another hybrid of literary and genre fiction.

A third classification

In addition to the two broad classes of literary and genre fiction (with, of course, subgenres of religion or spirituality in many flavors), traditional American publishing today distinguishes between the streams of ABA (American Booksellers Association) and CBA (Christian Booksellers Association). “Christian” writing, then, is a third entity, viewed by the publishing world as distinct from both literary and genre fiction recognized by the general market. Writers are forced to decide whether they are targeting secular or Christian readers, as most ABA agents and houses don’t accept explicit faith messages, and most in the CBA won’t abide the grittier aspects of violence or sexuality.

A true crossover between the world and the church doesn’t seem feasible unless publishing independently—outside of both CBA and ABA. I might wish that the distinctions would ease, as I attempt to write literary fiction with genre attributes available to the secular world but understood at a spiritual level. However, I suspect even more polarization is developing in our constantly changing culture.

Literary Fiction with a Theological Twist

As a reader, I crave the entertainment value of popular genre fiction, and yet I love to delve into deeper themes accessible through literary fiction. I’m saddened over the hollow feeling I’m left with by a strictly genre novel I can’t analyze for spiritual meaning, while I’m also overwhelmed by impenetrable ramblings when faced with an artsy literary read that doesn’t grip me through at least one or two genre conventions.

As a writer who is also a Christian, I don’t pen what many would call “Christian fiction”—I don’t swim too easily in that genre stream. At the same time, my own love of Scripture demands fictional expression. To top it off, most of my stories don’t follow rules of the main genres (for example, some of my romantic characters have their hearts broken and some of my endings are unresolved); instead, I try to use symbolism pointing readers back to the Bible.

(For more of my thoughts on this subject, check out my preceding post, “Read It Anew,” found below on this website.)

All of this is so true! Loved the quote from John Calvin! Without God we are nothing.

We owe all to God.